The massacre of Italian workers in Aigues-Mortes in 1893

This story is ideally the continuation of the New Orleans lynchings that took place only two years earlier.

It happened on August 17, 1893 and it was a massacre that time transformed into a symbolic story, given that this tragic chapter of Italian emigration abroad was triggered by a false report, it happened that ten Italians were killed by an angry mob, after decades in which he had built a negative stereotype of the emigrant of the Bel Paese, presented as "briseurs de salaires", a "thief labor." The workers of the region feared, in fact, that the massive introduction of foreign labor led to a decrease in wages and, perhaps even worse, to the questioning of their autonomy and their bargaining power. Worker nationalism, which combined protectionist will, traditional xenophobia, anti-German sentiment, and anti-Semitism, was present at least until the first decade of the twentieth century and some of its traces remained even later.___________________________________________________________________________

|

| siege of Paris |

|

| Sedan's Franco-Prussian war |

On March 18, 1871, the red flag flies over the Hotel de Ville in Paris: it is the symbolic beginning of the Commune, of the first revolutionary popular and workers' government. An experience of ephemeral duration (March-June 1871) capable, however, of representing a fundamental stage, a lasting reference, of the workers' movement and of scaring the European bourgeois class to death, reacting with ruthless violence to the emerging emergence of the class struggle.

__________________________________________________________________________________________

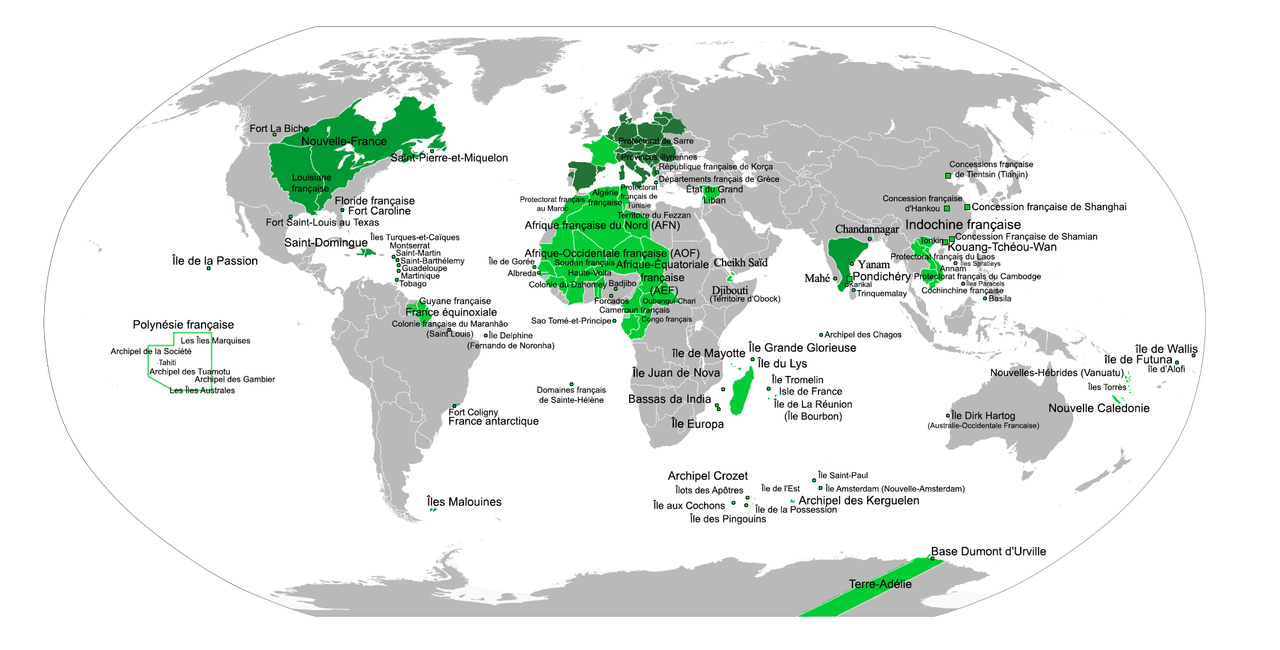

They are also the years of colonial expansionism with that much of racist ideology that it supposes.

| |||

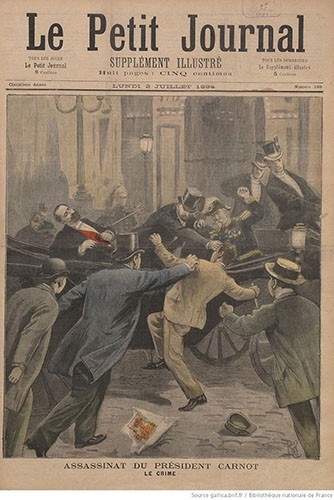

Carte-Anachronique-des-tout-les-empires-francais(1534-1980) ________________________________________________________________________________________ Representation of the assassination of Carnot appeared in Le Petit Journal Illustré.

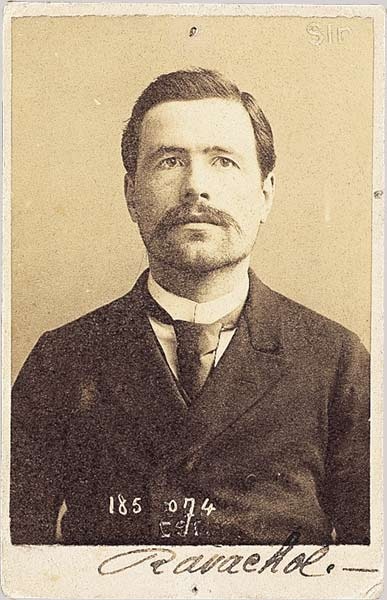

Italians are identified as people used to singing and begging; the stereotype of the sharpener appears (an Italian anarchist kills the president Sadi Carnot to avenge the death of the anarchist François Koenigstein, known as Ravachol) reserved for Italians at least until 1940, the date of the fascist aggression, not coincidentally defined "coup de poignard ".

________________________________________________________________________________________The anarchist song La Ravachole thus celebrates its struggle:"In the great city of Paris,There are well-fed bourgeois,There are the poor,Who have an empty stomach,Those have long teeth,Long live the sound, live the sound,Those have long teeth,Long live the sound,Dell'esplosion!Let's dance the ravachole, Long live the sound,Dell'esplosion!All the bourgeois will taste the bombs,All the bourgeoisie will blow up,All the bourgeois will jump! "in the first stanza of the Individualist Hymn:"Before he dies in the mud of the streetWe will imitate Bresci and Ravachol [...] » ________________________________________________________________________________________"The emigration of Italian labor, which at the mass level had begun in the years of the Second Empire of Napoleon III, was gaining more and more weight during the Third Republic. In 1876 there were 165,000 Italians in France, who constituted the 17th % of the entire foreign immigration: ten years later, they had grown by 100,000 units, exceeding 264,000 people and 24% of the total number of foreigners At the time of the events we are dealing with, out of the 38 million inhabitants that counted the country, the non-naturalized Italians exceeded 300,000 units. "Sulla xenofobia operaia in Lorena si vedano Y. Lequin, La mosaïque France. Histoire des étrangers et de l’immigration en France, Paris, Larousse, 1992, 395, P.-D. Galloro, Ouvriers du fer,cit., 39-41 e G. Noiriel, Longwy, cit., 78-80A. Perotti, La situation des immigrés italiens dans le bassin minier et sidérurgique du Luxembourg et de Lorraine avant 1914, «Studi Emigrazione», XXXVII, 138 (2000), 377-404 George Orwell's considerations are still relevant when he investigated the miners; in 1937 he wrote: "More thanevery other, perhaps, the miner can represent the prototype of the manual worker, not just because his work isso exaggeratedly horrible, but also because it is so virtually necessary and at the same time so far from oursexperience, so invisible, so to speak, that we are able to forget it as we forget the blood that is thereit flows in the veins (...) The same thing happens with all sorts of manual works, they keep us alive and uswe forget that they exist ”.________________________________________________________________________________________

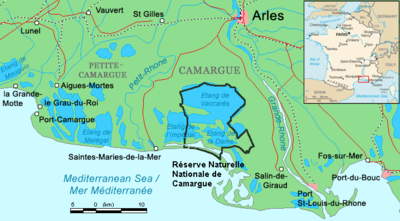

In this context, employers used xenophobia in times of economic crisis to expel excess labor, but they were also partially damaged, sometimes having to renounce the hiring of foreigners in order not to feed tensions. Overall, however, xenophobia did not prevent the entry of thousands of Italians, both in the mines of Lorraine (Sardinians in particular, who died prematurely due to diseases such as silicosis) and in the Camaurge, a wet and swampy area where salt was collected. The fights between indigenous and immigrant workers were quite frequent, these occurred mainly during periods of severe economic depression, the clashes were linked to socio-socioeconomic causes: more than 70% of the accidents occurred between 1882 and 1889, that is in periods of high unemployment and strong social tensions. "Persecutory acts against ethnic or religious minorities, conducted with the more or less declared support of authority".A strong demographic depression struck France on the eve of industrialization and the simultaneous launch of the imposing plan of public works commissioned by Freycinet, 4 times prime minister and minister of war in the Third Republic, favored the entry of migrants even in spite of all the laws prohibiting entry. A large part of this immigration, especially from Piedmont and partly from Liguria, was seasonal immigration, which concentrated near the communities already present in France and was supported by relatives and friends (half a million seasonal workers out of 750,000 emigrants) and Tuscany (200,000 out of 320,000).

________________________________________________________________________________________

Two are the reference books of the Aigues-Mortes massacre:

On both sides of the Alps, the management of immigration memory has various forms. If the glorification of emigrants left the end of the 19th century in Italy, the country faces the challenge of enriching its history with those who come to live there. On the French side, the memory of the Italian presence has gained visibility to prestigious ambassadors of the world of culture and sport. But it remains mainly the prerogative of the descendants of the migrants themselves. The awareness of the shared memory between France and Italy remains in the making.

That of Enzo Barnaba released in the centenary of the massacre and subsequently translated into French, although in the early years it was not sold in the localities where the events took place.

Barbana's work is divided into three parts: “In context "(to reconstruct the Italian emigration to the late nineteenth century, but also the French context, the campaigns xenophobes of the nationalists, the policies adopted),"The facts" (the work at the salt marshes, the accidents, the dynamics of the clashes end up massacre of 9 Italians, which does not take place as a single sudden accident but it is a real agony prolonged, the police will intervene 18 hours late) e"The consequences" (both political, with repercussions on the relations between the two countries, both social, with demonstrations in Italy, the reaction of the socialist parties of the two countries), up to the mockery of the financial trial, which sees the only condemned an Italian for resistance to public offices.

And the book by the French historian GÉRARD NOIRIEL

"Le Massacre des Italiens"

Despite the overwhelming evidence against them, the killers were all acquitted. This event put France at the mercy of European nations and brought it to the brink of a war with Italy. Finally, in order to preserve peace, the two governments preferred to bury the deal.

A recognized immigration specialist and the national question, Gérard Noiriel reopens this painful dossier and explains why the political and economic changes of the late nineteenth century have made such a massacre possible. How do official speeches about the pride of being French incite those who left the Republic to persecute foreigners? How leaders, soldiers, journalists, judges and politicians manage to escape their responsibilities.

The case of Aigues-Mortes also shows that when the power of the state prohibits "repentance", the guilt feelings of the actors or accomplices of a murder can be transmitted from generation to generation. Brilliantly concluding his "duty of history", Gérard Noiriel finally gives the slaughter of Italians in its rightful place in our collective memory.

Historian, director of studies at EHESS, Gérard Noiriel is one of the founders of the Supervisory Committee against Public Uses of History (CVUH).

_________________________________________________________________________________________

The Aigues-Mortes massacre happened in that year of elections, 1893, during a fierce electoral campaign. In August the nationalist writer Maurice Barrès, in Le Figaro, spoke of "invasion". He did it to defend the "special character" of the French identity, arguing that it was necessary to counter the invasion by enhancing the concepts of family, nation, and race. Barrès declared, frothing with anger, that the "hordes barbares" threatened work and represented a social, moral and political danger. The contempt and fear spread rapidly, also contaminating the vocabulary: in Nice, the term "Piémontais" was an insult. The barbarian hordes were the Italians, In the city of San Luigi, the Piedmontese worked more than the other saliniers. On the morning of August 16, a young man from Vernante, Giovanni Giordano, quarreled with the French, threatening them with a pitchfork. Bands were formed ready for battle, but nothing happened. At this point, however, everything was ready for the worst, for the Aigues-Mortes massacre. It began with a trivial accident (the quarrel) and degenerated into the slaughter of the Italians. The lynching of the saliniers in 1893, the false news was put into circulation by some French workers who, while returning on August 16 in Aigues-Mortes, ten kilometers from the salt pans, told of the unprecedented violence of the Italians, of people stabbed and mortally wounded.Aigues-Mortes. The first assault on the Fanhouse saltworks (from L’Illustrazione Italiana, 1893).A few words were enough to ignite xenophobic hatred. On the morning of August 17, the crowd, which had besieged the Italian refugees in some houses during the night, gathered with clubs, shovels, rifles, and pistols. The perfect and the mayor of Aigues-Mortes obtained the expulsion and dismissal of the Italians by the salt company, the powerful Compagnie des salins du Midi. Twelve gendarmes on horseback with Captain Cabley withdrew about eighty Italian workers from the salt pans, with the promise of escorting them to the town station and thus starting them by train to Italy, via Marseilles. Italian workers were surrounded, not protected against the throwing of stones. The first deaths fell. Only thirty-eight, now desperate, arrived under the walls of Aigues-Mortes, where the population was foaming with rage. A collective madness exploded and the massacre of the Italians began. Instead of being treated, the wounded were abandoned to certain death.The official deaths for the French authorities, in 1893, were eight and the identity of seven people were known. Recently, Enzo Barnabà added two more victims to these numbers. The certain deaths have thus risen to ten. The cuneesi Giovanni Bonetti, 31, of Frassino died, and Giuseppe Merlo, 29, of Centallo; the Turin citizens Vittorio Caffaro, 29, from Pinerolo; and Bartolomeo Calori, 26, of Turin; the Alexandrian Carlo Tasso, 58, of Cerrina; The official deaths for the French authorities, in 1893, were eight and the identity of seven people were known. Recently, Enzo Barnabà added two more victims to these numbers. Certain deaths have thus risen to ten. The cuneesi Giovanni Bonetti, 31, of Frassino died, and Giuseppe Merlo, 29, of Centallo; the Turin citizens Vittorio Caffaro, 29, from Pinerolo; and Bartolomeo Calori, 26, of Turin; the Alexandrian Carlo Tasso, 58, of Cerrina;the Astigiano Secondo Torchio, 24, of Tigliole, the Ligurian Lorenzo Rolando, 31, of Altare (Savona), Paolo Zanetti, 29, of Alzano Lombardo (Bergamo) and the Tuscan Amaddio Caponi, 35, of San Miniato (Pisa). On August 18, 1893, the bodies lying at the hospice were photographed by the French authorities for the purpose of possible recognition. At midnight, the bodies were interred. The seven coffins, carried on two carts, were followed by only two people. The perpetrators of the massacre, on the other hand, will all be acquitted of the trial that lasted four days, from 27 to 30 December 1893.Photo for the recognition of the corpse of Giovanni Bonetti (or Bonetto).A never-ending quest the time of the massacre in Aigues-Mortes there was the talk of hundreds of victims. The historian Enzo Barnabà also indicated these research points to the undersigned, regarding the missing: The Company did not know the names of the workers who made the collection. The list was drawn up on the basis of testimonies collected by the Consulate (like: "With me, there was XY that I have not seen") or received by letter to the same (like: "We think that our father, of whom we have no news, was in Aigues-Mortes "). The list of the 14 missings was made public in November; in the following months it shortens considerably: many "missing" were not at all such or are found in full form. None of the family members of the people who continue to be on the list - with the exception of Secondo Torchio's mother - will request compensation from the Treasury. The possibility of compensation was announced by the press, prefects, and mayors of the areas concerned. Everyone knew about it.No other bodyies- with the exception of Torchio - will never be found in or near Aigues-Mortes. The local pressBarnabà's research was conducted on French materials: the judicial documents in particular, which later disappeared and were later found.

__________________________________________________________________________________________

In fact, the Aigues-Mortes massacre marked a profound diplomatic crisis between Italy and France. In Genoa, Naples, and Rome there were serious incidents against French shops. We report, to understand the climate of those days, an article appeared in the Gazzetta di Casale (newspaper of the Diocese), entitled The massacre of the Italians in France, 26 August 1893:It has not yet arrived in the newspapers, nor with the telegraphic agencies, any serious consideration that serves to mitigate the gravity of the events of Aigues-Mortes. We, therefore, find ourselves in the presence of a brutal massacre of our countrymen, of a wild hunt to the man, who makes the massacres perpetrated by the African gangs, or by the tribes of the red skins, run into the second line. .......... Because we must not forget that the characteristic episodes of this slaughterhouse are in fact constituted by the proclamation of the mayor of Aigues-Mortes who calls "satisfaction" given to the French workers, the ostracism from the yards of the workers Italians obtained by similar means! And the refusal opposed by the hospitals of Marseille to welcome the wounded Italians, who were marveled by the last blows of those human beasts. Whatever may be the origin of the fight degenerated into a bloody massacre, very serious censorship always remains at the expense of those public officials, who, "si vera sunt relata", became unworthy of the honor of the office, to which the governmental trust he had raised. As for the poor Italian workers, forced by the harsh economic conditions, in which they find themselves at home, to procure themselves and work in France, we cannot but externalize all our commiseration and sympathy with them, and indeed with insults for squares and worse with riots and brutal scenes like in Genoa, in Rome and in some other city against people or institutions, innocent to the full and irresponsible of the atrocities committed by the French workers, we would like with firmness and serious protests to ask for the well due reparations and that with the help of the charity fraternal help was given to the survivors of the families of the dead.

Not to forget one hundred and twenty-five years later, the city of Aigues-Mortes remembers the atrocious massacre of Italian saliniers. A small step to recall the episode of 1893, until now erased from memory, as well as by the many guides dedicated to the city of the Holy King. On 17 August 2018, on the facade of the Town Hall, a small plaque was added, in the presence of the mayor of Aigues-Mortes, Pierre Mauméjean, the Municipal Council and the Consul General of Italy. On the plaque a period photo was reproduced, which depicts the bakery of Adélaide Fontaine in which many Italians found refuge during the massacre. The writing reads:In memory of the 10 Italian workers victims of xenophobia during the events of 17 August 1893. As a tribute to the just: Jacques Eugène Mauger (abbot), Adélaide Fontaine, nee Vical (baker), Madame Goulay. And to the citizens of Aigues Mortes who gave proof of courage and humanity.The dead, and those who tried to defend them from the beasts. Uselessly.

Not to forgetOne hundred and twenty-five years later, the city of Aigues-Mortes remembers the atrocious massacre of Italian saliniers. A small step to recall the episode of 1893, until now erased from memory, as well as by the many guides dedicated to the city of the Holy King. On 17 August 2018, on the facade of the Town Hall, a small plaque was added, in the presence of the mayor of Aigues-Mortes, Pierre Mauméjean, the Municipal Council and the Consul General of Italy. On the plaque a period photo was reproduced, which depicts the bakery of Adélaide Fontaine in which many Italians found refuge during the massacre. The writing reads:In memory of the 10 Italian workers victims of xenophobia during the events of 17 August 1893. As a tribute to the just: Jacques Eugène Mauger (abbot), Adélaide Fontaine, nee Vical (baker), Madame Goulay. And to the citizens of Aigues Mortes who gave proof of courage and humanity.The dead, and those who tried to defend them from the beasts. Uselessly.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wi...

https://en.wikipedia.org/wi... https://en.wikipedia.org/wi... http://ciml.250x.com/archiv... https://en.wikipedia.org/wi... https://fr.wikipedia.org/wi... https://en.wikipedia.org/wi... https://en.wikipedia.org/wi... https://en.wikipedia.org/wi... https://rivistasavej.it/la-... http://espresso.repubblica.... https://www.ivg.it/evento/i... https://www.infinitoedizion... http://www.altroviaggio.org... https://www.lastampa.it/ https://insorgenze.net/?s=m... https://storicamente.org/ https://fr.wikipedia.org/wi... https://fr.wikipedia.org/wi... JOURNAL ARTICLE

"Gli immigrati italiani in Francia alla fine dell'Ottocento e il massacro di Aigues Mortes

Giuseppina Sanna Studi Storici Anno 47, No. 1 (Jan. - Mar., 2006), pp. 185-218" (https://www.jstor.org/journ...

Coaloa R., “Uccidete i migranti italiani” 17 agosto 1893, la strage di Aigues-Mortes. Linciati dalla folla gli operai cuneesi delle saline, in La Stampa, 17 agosto 2018, pp. 28–29.

Cubero J., Nationalistes et étrangers. Le massacre d’Aigues-Mortes (1893), Paris, Imago, 1998.

Mourlane S., Païni D., Ciao Italia! Une siècle d’immigration et de culture italiennes en France. Sous la direction de Stéphane Mourlane et Dominique Païni, Paris, Édition de La Martinière, 2017.

|

Commenti

Posta un commento